Project Name: Riverhouse

Location: Puget Island, Cathlamet, Washington State

Size: 1900 sq ft

Designers: Louise Foster & Clive Knights

Riverhouse is a retreat for a retired couple residing in Portland, Oregon. It responds to their desire for a retreat close to the river and away from the city, a home from home in which to dwell amidst the vivifying landscape of the lower Columbia River. The clients talked of a place to watch the birds, a place to grow tomatoes, a place to make quilts, a place to return to from a kayaking adventure, and a place to gather their growing family around them. Though modest in terms of accommodation (2 bedrooms, 2 bathrooms) the clients also wanted the opportunity to create sleeping nooks for times when visitors were numerous.

The house sits against an existing dock on North Welcome Slough, a quiet waterway penetrating the low lying flatness of Puget Island, Cathlamet, and extending from the southern arm of the Columbia River as it wraps itself around the island. The Columbia valley spreads at this point, as the cliff-cut abruptness of the Washington bank becomes a softer, continuous edge of hills to the north, echoing the velvet green swathe of hills to the south, in Oregon. The presence of both the north and south horizons is overwhelming and emphatic, enhanced by the horizontal topography of the island that feels like a tentative solidification of the surface of the river, always at the mercy of the river's aquatic power, its potential to engulf and to wash away, and yet also to sustain.

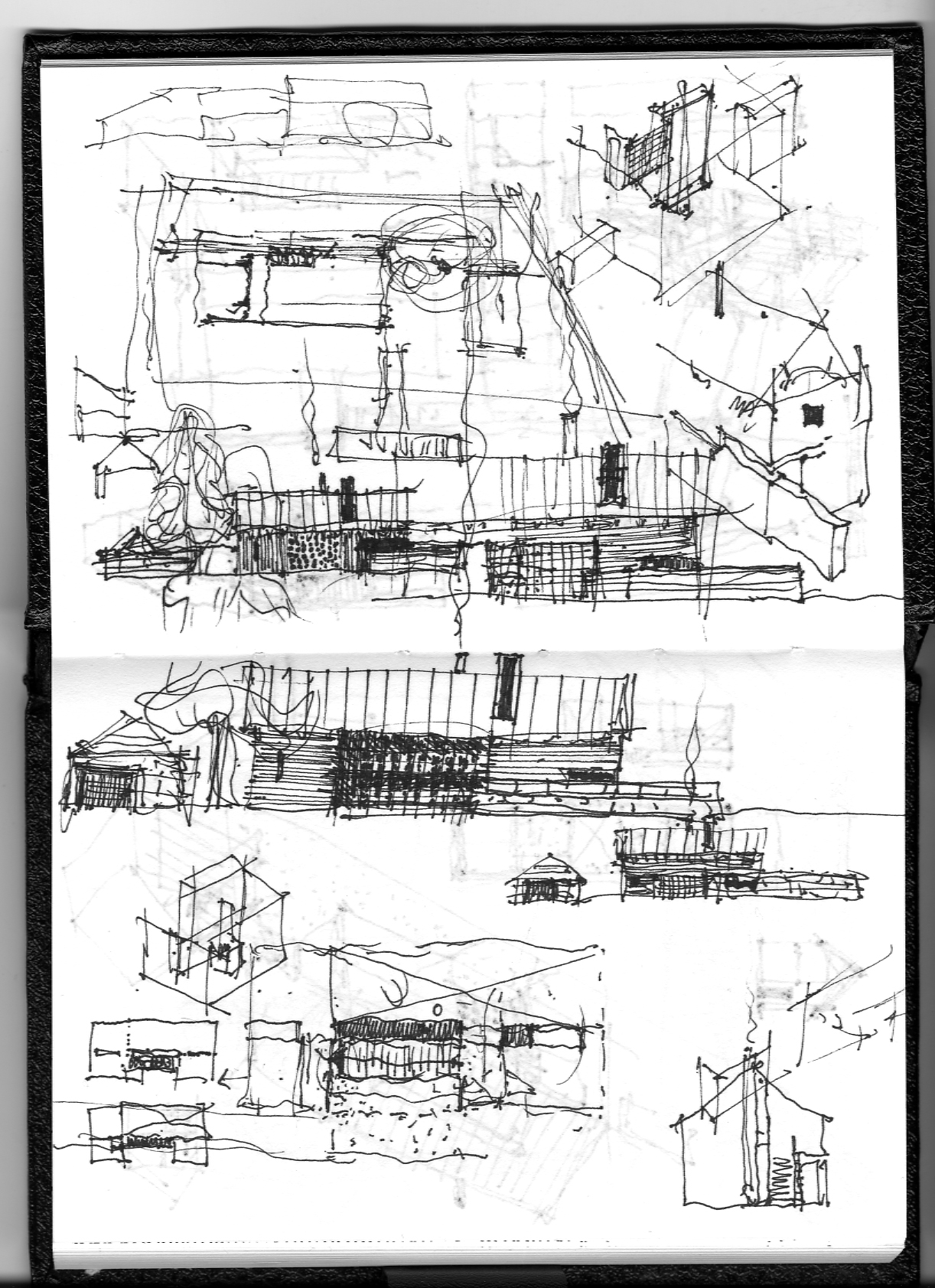

This landscape is a primary design inspiration. How can architectural intervention mediate the vastness of this terrain with the intimacy of human dwelling? How can it reconcile the pervasive strength of one of North America’s great watercourses with the fragility of human life, unrelenting flow with finitude? And how can a creative response address themes of the river, its aquatic presence, leveling, buoyancy, gravitational pull, and so on? These questions generated several design responses:

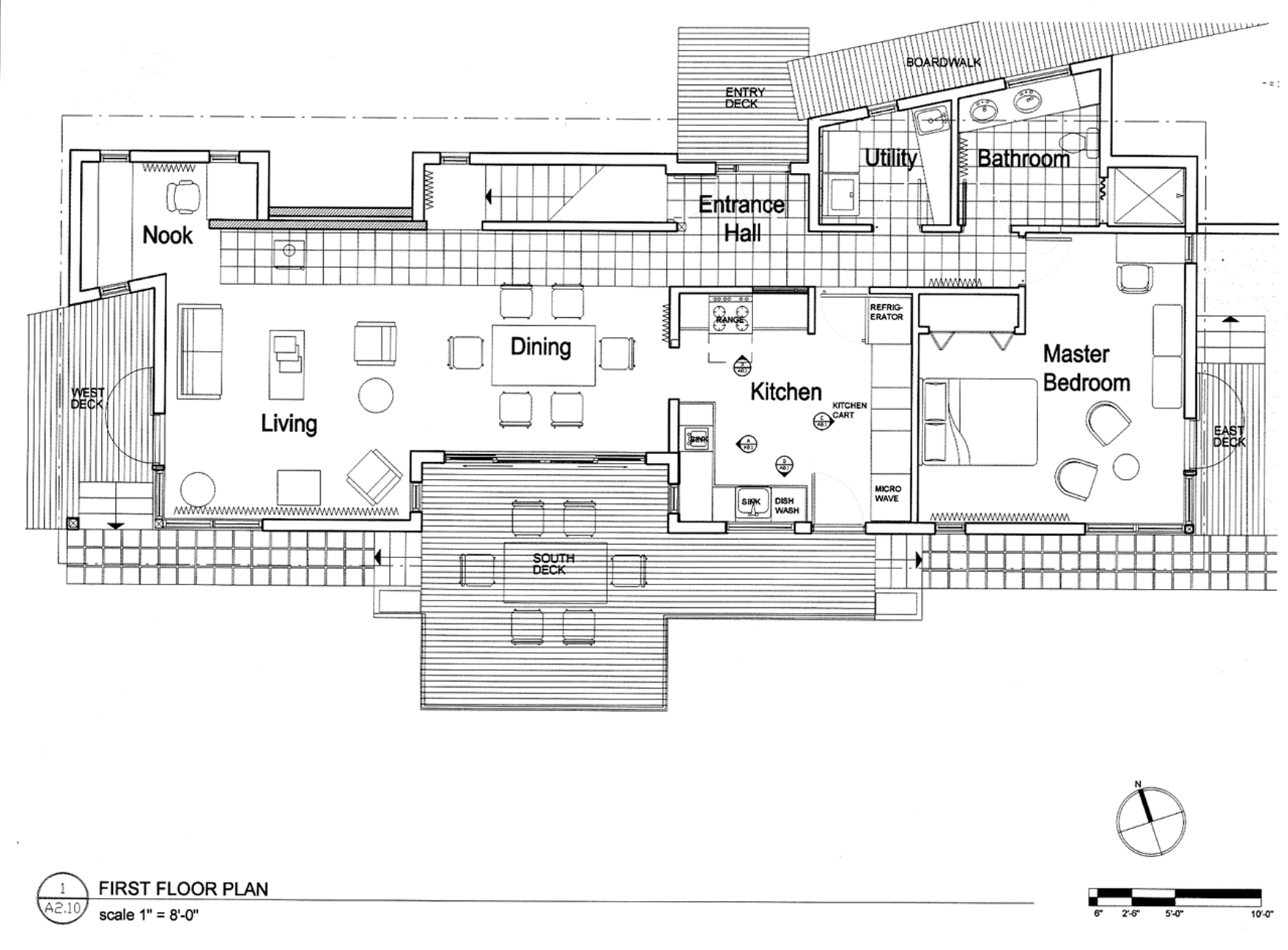

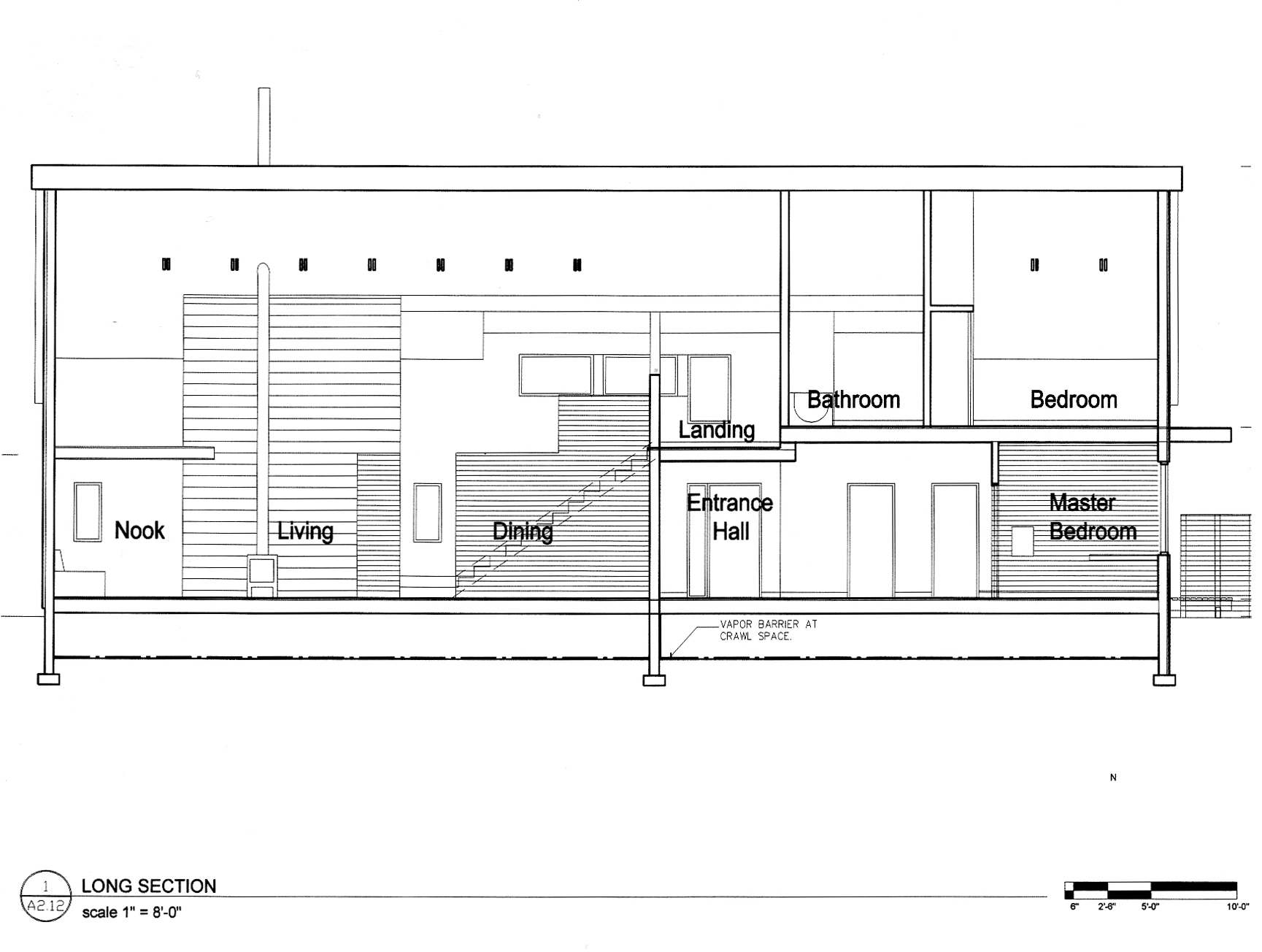

1. The house is essentially a simple rectangular volume, 65ft by 22ft, set down with its long edge parallel to the slough, anchored at the edge of the constantly moving water by the perpendicular projection of the existing wooden quay. North Welcome Slough Road runs parallel to the slough along the north side of the lot, and when already established mandatory setbacks were taken into account the maximum width of footprint possible was 22 feet. The house replaces an existing dilapidated manufactured home. The main entrance is along the north façade with the south façade opening up to the water’s edge. The simplicity of the main volume makes reference to the simplicity and stoic persistence of the many barn structures typical of Puget Island, left over from the island’s dairy farming past. The unity of this volume is reinforced by the consistent use of colored lap siding. Modifications to this unified volume take the form of extrusions or excavations, pushing the inside out or pulling the outside in, and are signified by a deviation from the common lap-siding through the use of natural cedar or masonry block. The simple double pitch roof is also modified in places, pushing up into two dormers like hinged hatches, a partial lifting of the lid of the volume in response to the landscape.

2. The journey to the house follows Highway 4 west from Longview, hugging the rocky north bank of the Columbia River. The road alternates from water level to hill top, at times chiseled from the base of rugged cliff edges just feet from river waters, and at other times soaring up through woodlands that intermittently offer framed views of the lower reaches of the river. The rhythm of this above and below alternation, combined with the flow west and what feels like a primordial dialogue between horizontality (extensive water surface) and verticality (sheer rock wall), is translated into the linear disposition of the house plan, and the articulation of elements in the main living space.

3. The approach to the house by road is from the northeast and as such the south horizon of Oregon hills dominates. A single evergreen tree acts as a vertical marker introducing the entry ramp rising from the parking area in front of the detached garage. This ramp slides obliquely alongside a cedar clad extruded volume, up to the entry deck and front door, a warm, natural surface to guide and to greet. As if approaching a riverbank from the water by kayak, arrival is never frontal and perpendicular to the facade, but rather a negotiation of edges and countering forces. Rising up the entry ramp, a horizontal projecting cedar sill creates a visual datum, a level, in contrast to the incline of the ramp. Here, the north horizon is predominant, as the bulk of the house shields the view to the south.

4. On entry, as one’s back is turned to the north, a framed glimpse of the south horizon opens up through a small opening in the south wall of the entry hall just as boardwalk becomes slate underfoot at the threshold of the front door. The slate is ambiguously ‘terra firma’ at the same time that it is steely green-gray aqueousness. It stretches east and west, along a single alignment parallel to the waterway and signifies an internal flow or circulation through the house, and a notion of boundary between north and south that reiterates the Columbia’s own effect of division on the landscape.

5. The scale of the main living space with its double height vaulted interior attempts to reconcile the scale of the human body with the pervading vastness of the valley. The pragmatic necessity of a living/dining space, with its furniture informed closely by the finite measure of the body, is challenged by a desire to receive and converse with the infinite measure of the topographic setting. This manifests as excess, as hollowness, as 'more than' as opposed to 'tight fit', not in a quantitative sense (more square footage) but rather in a qualitative sense, attempting to bring the influence of vastness to bear upon what is in fact a very modest space (in square footage terms).

6. Rising from the slate floor on the north side of the vaulted living space is a 14ft high masonry wall, made with white concrete blocks and providing a backdrop to a wood burning stove whose flue rises vertically to the roof. This wall reiterates the verticality and sensuality of the river-cut cliffs and offers a sturdy sense of protection from the cold arctic winds from the north. It also has a special relationship with the sun in two ways. Firstly, by the deliberate placement of skylights high in the south slope of the vaulted roof, direct sun projects parallelograms of transient light onto the surface of the wall, tracking a unique path throughout each sunny day that traverses from top to bottom. Secondly, the masonry acts as a heat-sink, absorbing this solar energy for later release. A small reading nook is tucked behind this wall as a warm refuge in which to retreat from the loftiness of the main space.

7. The framing of the horizons to the north and south through the placement and character of window openings attempts to make the backdrop of the terrestrial horizon always visually present, and therefore always a participant, in each foreground activity taking place in the house, informing the particularities of domestic events, such as washing the dishes, reading a book, keeping warm by the stove, waking in bed, surfing the internet, eating dinner, rising and descending the stair, performing ablutions, and so on. The idea is to allow the dweller to be always aware of where they are in relation to that pervading vastness, to connect the mundane with the transcendent many times over, and potentially, in the midst of even the most habitual, even trivial, of tasks maintain a more profound and more meaningful sense of place and belonging.

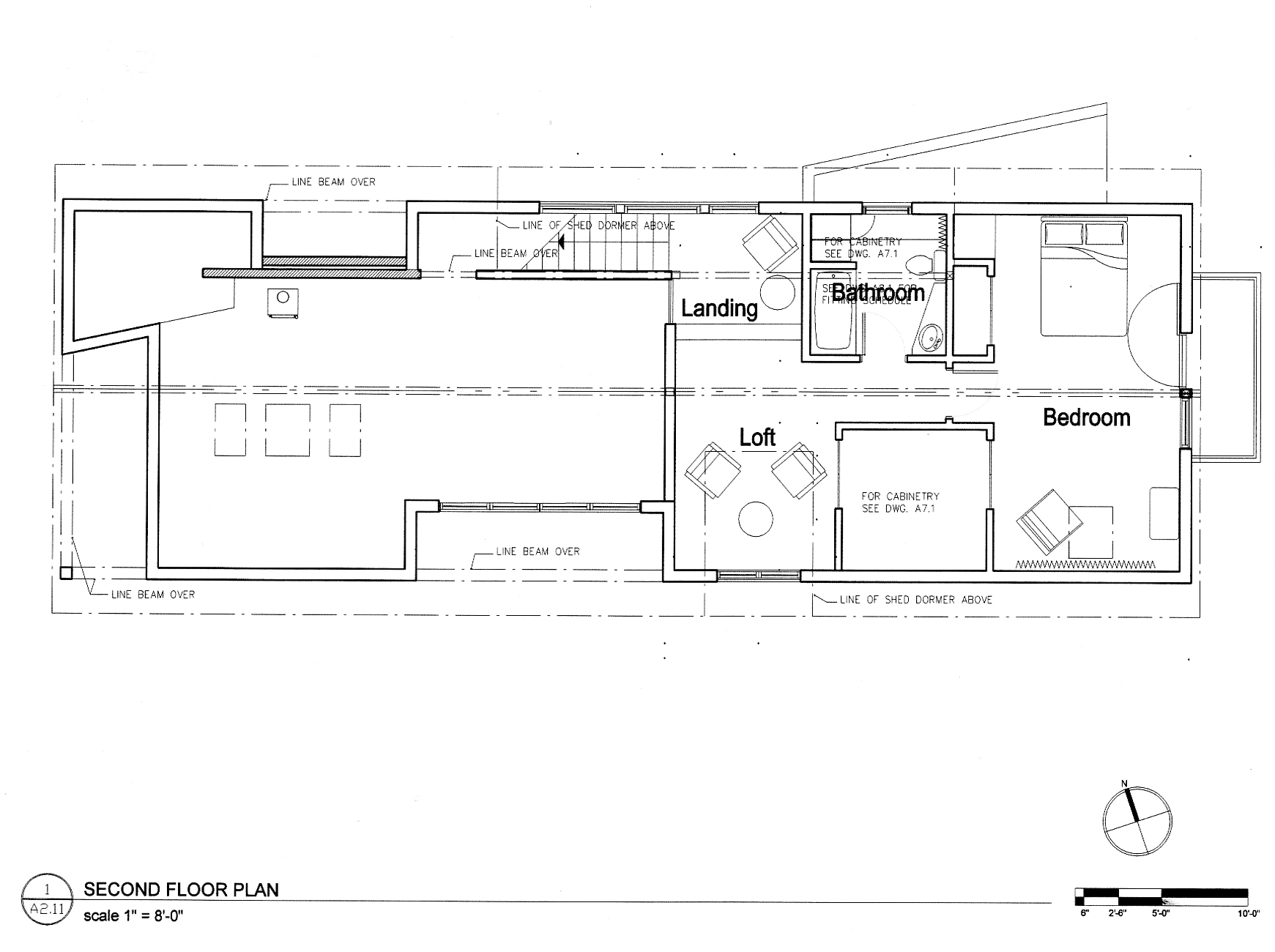

8. Windows on the north façade are small punctures in the protective surface of the north wall except in the north dormer where they come together to offer a panorama of the north horizon from the top of the stairs. Windows on the south side are quite different in intent. Large corner combinations, with French- doors opening onto decks, in the living room at the west end of the house, and in the master bedroom at the east end, offer oblique visual connection to the slough encouraging views upstream or downstream, bringing the linear extension of the waterway, and a greater perception of its flow, into the house. In the dining area a 14ft high bank of openings, including large sliding doors, floods the center of the house with light. These are set into a cedar clad recess connecting to a large deck that extends the dining space outside towards the water’s edge.

9. The stairs rise from the living area, ascending to the east, descending to the west, like the river. By the articulation of the enclosing walls to the stair attention is focused to the south horizon on the lower part of the stair, and on the north horizon on the upper part. The stair rises to a large landing and then up a few more steps to a loft space with a large double opening window overlooking the slough and on axis with the ramp of the existing quay. The loft has an open gallery that overlooks the dining and living space and is intended as a quilt-making area, doubling as a sleeping loft when needed for guests. It has a large storage space immediately adjacent, and a centered hallway leading back along the ridgeline to a second bathroom and vaulted bedroom.